Sex in the City: Reactionism, Resistance and Revolt – AAG #Geosex16 sessions in San Francisco (March/April 2016)

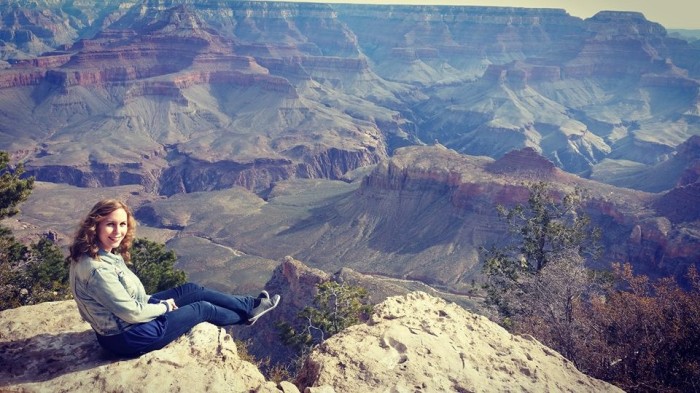

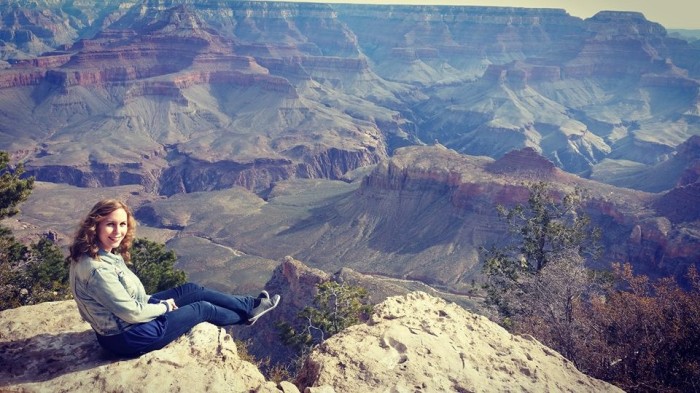

A couple of weeks ago I returned from the Association of American Geographers conference in San Francisco. The conference was a great opportunity to catch up with friends/colleagues (old and new!) and San Francisco was a lot of fun. I also had a week in Las Vegas, where I did a talk at UNLV and lots of holidaying. Taking a drive up to the Grand Canyon in Arizona was definitely a highlight. Here is me on my first look out:

Now onto our #geosex16 sessions. Paul (@planographer), Martin (@Zebracki) Clarissa (DrClarissaSmith) and I were completely overwhelmed with the response that we got from the call for papers and the sessions went really well. We had a range of presenters, including academics (early and established careers), sex workers, sex worker academics and the quality of papers was excellent. Here is Paul’s interview with Xbiz.com about the sessions: http://business.avn.com/articles/novelty/Sex-Work-to-Receive-Platform-at-AAG-Annual-Conference-640645.html.

I tried to take some notes during the sessions in order to be able to report on some of the papers in this blog for those who couldn’t attend. Some are more comprehensive than others – this was due to me having to undertake chairing duties/wrist-ache and/or I was charging the laptop. I have incorporated elements of the paper abstracts with the notes taken by me to enable some of the gaps in note-taking to be filled. Due to my over-enthusiastic note-taking(!), I’ll be posting the entries session-by-session.

Session I – Performance, Production & Politics

Zahra Stardust (@ZahraStardust) (University of New South Wales): “Queer feminist pornography as a social movement: Protest, resistance and radical politics”

Zahra kicked our sessions off excellently, with her paper about queer feminist pornography. Based upon 19 qualitative interviews with porn producers, Zahra’s research explores how they maintain political integrity and ethics whilst navigating the regulatory framework. She argued that porn acts as a protest mechanism against state censorship and government intervention while also deliberately and poetically violating laws designed to closet non-normative practices.

As Zahra outlined, in Australia, the production, exhibition and sale of pornography is criminalised, attracting fines and imprisonment; thus, porn producers are ‘sexual outlaws’. Customs and Classifications have prohibited pornography depicting female ejaculation, small breasts (which look ‘underdeveloped’), genital detail and fetishes (eg BDSM). Resistance to such laws include the recent ‘face-sitting’ protest outside Westminster (UK) in 2014. Despite this, Australia has a queer feminist porn community whose work receives notoriety worldwide.

Zahra explained how shooting porn is a guerrilla operation. Porn sets operate as temporary autonomous zones (such as warehouses, the bush, backyards), organised by word of mouth in transient locations. Smartphones are also turned off to avoid identification by authorities. Porn production involves skill-sharing, resource-lending and a DIY approach with the capacity to create mobilised, empowered communities. New technology has democratised porn: of which there is a multitude of different types. Zahra outlined how the producer, distributor, consumer boundary is now much more blurred, and who can produce porn/who can represent others is also now changing as a result. Performers are becoming directors, and directors are becoming facilitators; enabling more control of representation and revenue, and helping the performer’s experience to be prioritised (eg the micro-geographies of working conditions). Therefore, more collaborative and facilitative models of production are forged, and performers can more readily ‘forge one’s own space instead of looking elsewhere to be represented’, which is creating more ‘participatory spaces’, as well as greater potential for entrepreneurial opportunities.

Zahra’s research shows that production fosters an ‘ethics of care’ and ongoing dialogue about community standards that resists patriarchal state regulation. Zahra argued that ‘leaders abdicating power is the future of queer feminist and ethical porn’, with a redistribution of wealth and a trickle effect on every other aspect of the business being possible. Due to the “accountability to community” that ensues from the blurring of roles (as opposed to the producer-performer boundary being clear-cut), this also improve working conditions, health and safety, and creates clearer policies and better contracts for performers.

I particularly liked Zahra’s final statement: that porn is “art, work, and business”, with binaries in class and taste being presented as “good” or “bad” porn being unhelpful. She stated that “it is essential to tackle stigma directly” instead of such unhelpful categorisations, in order to more effectively tackle issues such as exploitation and to ensure appropriate working conditions for performers.

Gemma Commane (@GemCommane) (Birmingham City University): “RubberDoll: The Queer Art of Failure and the Significance of Sexual Otherness”

Gemma’s powerful paper presented a case study of RubberDoll (http://rubberdoll.net/): a hard-core fetish latex model, performance-artist and full-time kinkster. Gemma outlined that the Rubberdoll brand originated in the 1990s, with photos of her modelling rubber clothing, and progressed to performances at clubs etc (of which there is a high demand for appearances). The act includes multiple ways of expressing sexuality, and is more dominant than submissive – which is evident in stage shows, dvds etc. Gemma outlined that “latex is a flexible subject”, which has the ability to embrace “pervy heavy rubber” and elegant “couture”.

Gemma argued that RubberDoll’s latex-encased lifestyle and artistic expressivity is cleverly mixed across and within a range of hybridized forms of technologies and leisure-time environments, where she continuously presents a journey to the outer-limits of fetish and kink. The social nature of the spaces of performances, Gemma explained, enable great opportunities for personal expression and to explore self-identity. Such spaces also cater for Rubberdolls’ sexual appetite and preferences, reproducing them via music choices, act choices and ambience – “irrespective of external ideological forces which represent her as a failure of femininity, morally corrosive and dangerous”. The creativity in crafting such performative spaces and use of layers in performance is “artistic gendered activism”.

Using Ahmed’s definition of queering something as to ‘disrupt the other of things’, Gemma argues that via managing herself and expanding on how (her) sexual expressivity and kink can be communicated, RubberDoll queers the cis-gendered male gaze and develops the political significance of sexual otherness. I think my favourite statement of the paper was that “alternative feminists should be valued as socially and politically significant: acts like Rubberdoll are reproducing alternative routes to success”. Gemma outlined how repressive ideological values, which deem ‘Other’ women such as Rubberdoll as insignificant due to their lack of ability to conform to heterosexual norms (eg relating to coupling, intimacy, desire and pleasure), can and should be disrupted. Rubberdoll’s failure to conform and radical undermining of normative scripts, Gemma stated, is not only important in seeing identity as having endless possibilities (e.g. that femininity is not owned by one type of woman only, and is not one-dimensional), but it has been key to her entrepreneurial success. Her business empire has survived multiple barriers against female entrepreneurs such as status, networks, funding and she is now one of the top fetish artists. As Gemma’s abstract states: “this has also been in the face of the issues and tensions that intersect and are expressed when a woman engages with pornography, sexual deviancy, and kink. This makes visible the potential of a flexibly-queer community of difference, where kinky-queer women are able to live their self-identity both personally and professionally”.

Lucy Neville, BA (Hons), MSc, PhD, PGCertHE (@blue_stocking) (Middlesex University): “A Forum Of One’s Own: Female Slash Writers And Online Embodiment”

Lucy’s paper drew on a piece of wide-scale mixed-methods research (n=351) that examined how women who write gay male erotica and pornography utilise online spaces as places for exploring their own gender and sexuality. Her research investigates the ways in which online space provides what is perceived by participants as a ‘safe’ environment for creatively examining issues around gender, sexuality and sexual performance – particularly challenging heteronormativity and gender conformity. Lucy drew from Feona Atwood’s extensive work, arguing that the boundaries between online erotic content and real life sexuality can be blurred via such spaces. Previous work has looked at how online slashfic communities might provide a space for exploring gender performance and sexuality in a way that constitutes Foucault’s vision of ‘creative practice’ as a form of political dissent (Hayes & Ball, 2009).

Other work has observed a tension between writers and readers who see the online community as ‘safe queer space’ to explore their own lived queer identities, and those who only ‘play at queerness’ exclusively within the online environment (Lothian, Busse, & Reid, 2007). Lucy argued that, as the virtual plays a constitutive role in the materialization of gender, sexuality, and embodiment in both digital and physical spaces (van Doorn, 2011), the distinction between ‘online’ and ‘lived’ experiences needs to be better examined.

Lucy’s findings suggested that the online can provide a narrative safe haven; to develop the strength necessary to find a sense of belonging and meet like-minded individuals. She also discussed that the action of writing and consuming gay male erotica, for her participants, isn’t just about sex, but about having an online space, free from heteronormative conditions, where they can talk about life and sexuality in a way that is less restricted by such boundaries. Lucy discussed the importance of spaces in the public sphere for subcultural practices, be they physical or virtual, and for changing political views more generally.

Some of the underpinning questions to Lucy’s research included: does tension exist between authentic queer experience and queer tourism; and how do the women in these communities feel about it?

Some findings: the majority of respondents said they used material to masturbate, that it wasn’t just a political crusade (although 68% of what participants read or watched had some sort of political angle, e.g. seen a gateway to activism), but had a tremendous important role in their everyday practices/lives. The majority were against the shaming of women’s sexual fantasies/practices. One highlighted quote from a participant was: “it made me more open about accepting/understanding people who are not sitting in one labelled box”. Lucy outlined that there was also cross-identification and fluid gender identification going on within the sample. She did outline, however (although in the minority), that some participants experienced backlash for using the spaces – one having been called a homophobe, and one stating that “as a woman my experiences are considered invalid”. Generally, though, the space is seen as inclusive and also a space to learn – to open up beliefs and to expand knowledge about sexuality, gender, and sex. Also, it is considered a space to be happy – “gay guys are never allowed to live happily ever after in literature; one or both end up dead!”.

Prof. Clarissa Smith (@drclarissasmith) (University of Sunderland): “Because life without porn would be boring.” Thinking about Young People, Pornography and Everyday Spaces”

Clarissa’s paper centred on recent moral crusades regarding the ‘pornification’ of society and changes in UK legislation, with a particular focus on how young people have been described and problematized in such discourse. She discussed how arguments about pornification offer a view of public and private spaces as entirely permeated and shaped by pornography. In relation to young people, she argued, such talk conflates a range of issues: about protection, childhood, space and place and privacy. The range of recent UK legislation, she states, has sought to ‘protect’ young people and to keep ‘vile images’ out of the home.

Clarissa argued that such legal and protectionist discourses have marked the Internet as a major threat to the sanctity and innocence of the family home; cyberspace is figured as an alluring yet dangerous space for young people. In the UK, 3 major reports have been written for government since 2008, with changes being made such as ‘opt-in’ adult content filters online, and age verification. These adaptations have also been accompanied by documentaries such as Porn on the Brain (Channel 4) – which insinuated that pornography is ‘turning our children into psychopaths’. Clarissa highlighted how ‘exposure’ gets used over and over again in legislative discourse, with porn considered ‘a poison in the home’ (Fagan), putting our children ‘in harm’s way’. Such documentaries and legal discourses also discuss addiction, with consumers being portrayed as either victims or as having become perpetrators. Some of the imagery used in media include “bags under ‘Charlie’s eyes, his spots, his moodiness, etc’” as being directly a result of porn use by young people. Clarissa also outlined how the documentary “used pictures of the home in very particular ways eg young people making cakes with mum”; contrasting the differences between ‘other’ activities and what ‘should’ happen in the home.

Clarissa also outlined how concerns surrounding engagement in non-normative sexual activities e.g. anal sex, and the nostalgia for another time are encapsulated in the motivations for UK legislation change – the notion that porn used to be different (Dines) and fears around where/what it will lead to next. A key claim, she argued, is that “porn has developed outside the knowledge of ordinary parents/adult and needs urgent redress”. The dominant model, she said, is that porn is a singular form, it slips under adult radar, is portrayed as a new phenomenon, and the remedies are clear. The role of the Internet as a socialising space also comes into such discussions. However, she argued that ‘the social relations through which young people engage with pornography are rarely examined’, and certainly not with a critical lens that does not singularly centre on young people as victims. The complexities of young peoples’ use of the Internet as a means of escaping adult interference whilst also a space of parental surveillance are ignored in most policy investigations. Her research, including a complex online questionnaire (100 under 18s) combining quantitative and qualitative questions into the meanings and pleasures of pornography, challenges these accounts. The data complicates any notion that young people encounter sexual media by inadvertent ‘exposure’ to it and suggests that sexually explicit materials have intricate connections to young peoples’ understandings of family and the household space, and have multiple significances for their senses of themselves as sexual subjects.

Some findings: the home, which is generally seen as a place of safety, was also considered a “place of secrets” by participants. Participants discussed understanding that ‘adult things were going on’ and wanting to know what they are. She outlined narratives including looking to find out what the adult secret of sex was eg under beds, in cupboards. The internet is seen as a vast playground in which young people want to map their own ways through, and that young people eventually move into spaces of their own via preferences – “rather than the degenerative ‘slippery slope discussion like we get in policy reviews, ‘ending up’ in fetish material”. Clarissa also outlined that what people mean by ‘fetish material is not necessarily antagonistic, violent material’ – nor that exploration is simply a one-way street, moving backwards and forwards; people do have histories and connections with porn over time. She finished by discussing the play-off between kinds of ways of thinking about porn as something to enhance one’s life/be playful, but also that it can also be a part of one’s identity, reflecting something about oneself.